Ce pas à pas présente un projet en cours de réalisation.

Ce pas-à-pas est un bloc notes rassemblant les informations que je trouve sur les meules en grès.

Il fait suite à mon châssis de meule, que je ne voulais pas surcharger d'informations.

Les articles arriveront au fur et à mesure de mes recherches et lectures.

Pour la synthèse, il faudra donc probablement attendre

Liste des articles

Extraction et taille d'une meule en grès de 2m30 de diamètre

Making a grindstone in the sandstone pit

Herstellen eines Schleifsteins

Série de 6 vidéos du Digital Heritage Service allemand montrant l'extraction et la taille d'une grande meule en grès. Dommage que les sous-titre ne soient pas traduits en anglais ou français. La même vidéo en un morceau (l'ancienne avait disparu)

Mais à quoi donc que ça peut servir une telle meule ?

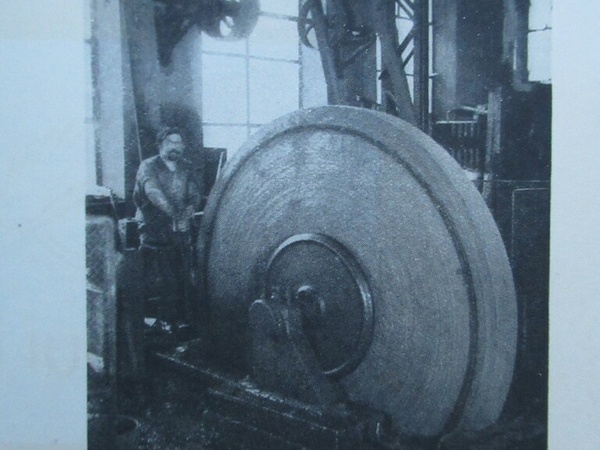

Et bien tout simplement dans une usine Goldenberg par exemple !

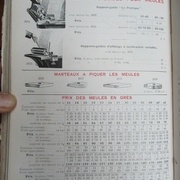

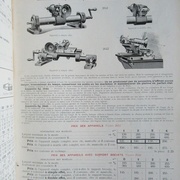

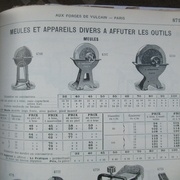

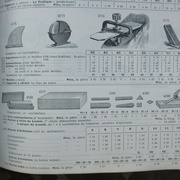

Aux Forges de Vulcain, 1912

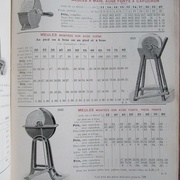

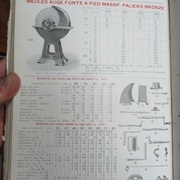

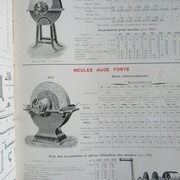

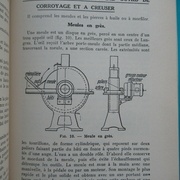

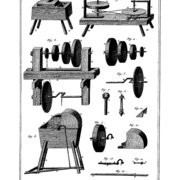

Dans cet ancien catalogue Aux Forges de Vulcain de 1912, dans le fascicule n°3 "Machines-Outils pour le Travail des Métaux", on trouve quelques pages sur les meules en grès.

On y trouve les articles suivants:

- des meules:

- à supports (chêne, fonte, fer),

- et entraînement (pied, main, moteur) variés;

- des accessoires pour ces meules (pièce détachées);

- des marteaux à piquer les meules;

- des appareils pour repasser et redresser les meules en grès.

Ces deux derniers points sont intéressant et donnent une idée de la manière avec laquelle les meules étaient "remises bien ronde".

Dans le fascicules n°4 "Outillage pour le travail du bois", on retrouve également une page consacrée à l'affûtage et contenant des meules mais également des pierres Arkansas, du Levant et India.

Roy Underhill : grindstone (or sandstone, or whetstone, it is the same!)

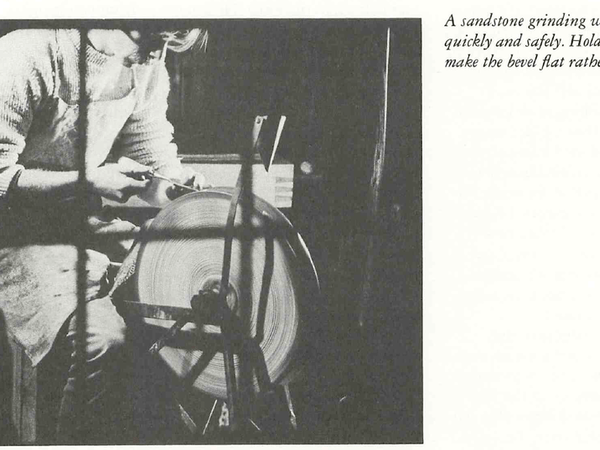

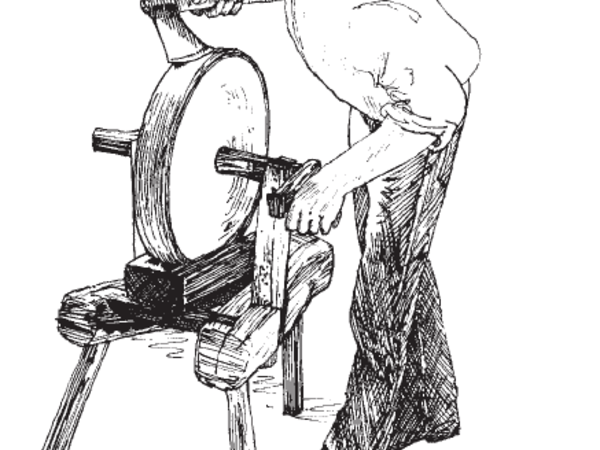

Dans ce livre, Roy Underhill présente sa manière d'affuter les outils avec une meule en grès, et comment contrôler cet affûtage:

I grind my tools to shape on a footpowered sandstone grinding wheel. It cuts fast, never overheats the tool, and puts on an edge that is fine enough for many jobs If you are looking to buy an old used sandstone, pass up one that looks as though it has been left standing in water in a trough set beneath it. A sandstone must be kept wet as you use it, but if it is left standing in water, it will be softened on that side and quickly wear out of round.

As you grind the bevel of a tool to shape, you will reach a point when the metal on the Very edge will be worn so thin that it no longer has the stiffness to press against the stone and will begin to form a fine feather edge. When this happens, it's time to move to a finer stone. I usually remove the feather edge by working it back and forth With my thumb until it all breaks off. The final honing and polishing must be done with very fine stones. I like stones that can be used with Water rather than oil and almost exclusively use White clay stones that are made for sharpening Straight razors. I have never bought one of these new because they generally run about twenty-five cents at flea markets. They cut quitk and hone the edge as sharp as I ever need.

To check the flatness of the flat side, I hold it down Hat on top of my left thumbnail and try to shave off a curl. If I have to tilt the tool up to get it to grab. I know that the flat side is rounded over. This side must then be polished flat or the edge must be ground back on the beveled side until the rounded-off length of the flat is removed.

Puis Roy Underhill raconte une annecdote sur le sens de rotation de la meule:

I met the Deacon years after he had retired. His shop had changed hands and fallen into disrepair. He knew how interested I was in the old ways, and so we would talk for hours about red-heart cypress, bench drills, wheelwrighting, wrought iron, and the like.

I once asked him, as one who should know, which was the best way to turn a wet sandstone grinding wheel, toward or away from you?

“Always away from you," he said.

Now, I had been at this long enough to have formed the opinion that there is seldom one right answer to questions like this. Seeing that he was not going to carry on with any futther explanation, I proceeded to expound on the debate as I understood it.

“Well, you know," I said, “I've heard both ways; some want you to go away from you so that the heat will be carried away (from the edge of the tool. Now, I know that the water dripping on the sandstone keeps it from ever getting very hot so that can't really be important. Some say you want to go towards yourself and the tool so that you won't draw out a wire edge and you can get it sharp faster. But you say away from you is right,"

“Always go away from you," he repeated.

“But why is that? What are you doing to the edge that makes that better? Do you want to draw out a wire edge? Is that why you do it?"

“No," he said, laughing. “If you turn towards you. you throw water in your lap."

Dans ce livre plus récent, Roy Underhill revient sur la meule à grès. Il parle se sa conservation, son utilisation et -encore une fois- son sens de rotation:

Grindstone

Axes, saws, and augers are tempered so that you can sharpen them with a file. On most chisels, gouges, adzes, shaves, and knives, however, a file will skate off the hard edge. These hard-tempered tools must be sharpened with a stone, and even those tools that a file can cut will benefit from the finer edge produced by the whetstone. The whetstone gives the final polish to the edge, but the work begins with the coarse grit of the sandstone wheel.

When you acquire a good sandstone grinding wheel, you become the guardian of a fragile treasure. Knock it and it will chip. Let wet wooden wedges expand in the axle hole and the stone will split. Leave it in water and it’ll go soft. Leave it in the sun and it gets too hard to cut. Leave it unattended and someone will dry grind a bolt head, leaving a deep groove in the face.

The fragility of these stones has even created controversy. Some people believe that a stone turning away from the tool gives a better edge, but most insist that the advantage runs the other way. Some, like my grandfather, turned the stone away from themselves because they just didn’t like water being thrown in their laps. The real difference comes down to this, whether the stone is lumpy and bumpy or not.

Turning toward the edge cuts faster, as the wedging action pulls the steel into the stone. Sadly, many sandstone wheels have been left sitting in a water trough at some point in their lives. This irreparably softens the stone at the waterline, leaving two points on the circumference that quickly wear into hollows. An edge tool dipping into one of the hollows tends to dig into an approaching stone, and the only remedy is to turn the other way.

Water is the friend and enemy of sandstone wheels. Dripping from a suspended can or held in a trough below, water washes away the dulled grit and steel particles ensuring a constantly fresh cutting surface. Water cools the heat of friction and protects the temper of the tools. But left sitting partially in water, the stone is ruined.

As with any stone, try to avoid putting grooves in it by constantly moving the tool back and forth to use the whole face. And don’t think a sandstone wheel won’t cut fast. Especially when turning away from you, a long wire edge can hide the fact that you have ground away a quarter inch of your blade, and that you should have moved on to the whetstone five minutes earlier.

Grinding is the first step of creating an edge. The coarse grit of the sandstone cuts fast but leaves a scratched and sawlike edge. The grindstone does the shaping — the honing comes later. The ideal shape for any given edge tool depends on the steel and the job, but a good starting point is 30 degrees. You can easily eyeball a 30-degree angle by grinding a bevel until it is twice as long as the tool is thick at the end of the bevel slope.

Grinding is reserved for the bevel side, but check the flat face to see if it is rounded over. In planes and chisels, you can’t get a proper edge until the flat face is flat all the way to the edge. If the flat is badly rounded over, grind from the bevel side until you cut back to a level surface. In rare cases where a tool is heavily corrosion-pitted on the flat face, you might try to save it by grinding the flat. The flat face is the side with the hard layer of steel that forms the edge — grind it away, and you have a paint can opener.

Livres de menuiserie et d'affûtage

Le livre de Heurtematte traite -bien entendu  - des techniques d'affûtage et en particulier des meules. Allez donc voir les pages 74 à 77. Meule en grès:

- des techniques d'affûtage et en particulier des meules. Allez donc voir les pages 74 à 77. Meule en grès:

- caractéristiques des meules;

- avantages de la fontaine d'arrosage;

- rectification des meules (à sec avec une queue de lime ou un tube en acier trempé).

Traite également de la rectification des meules. Méthode présentée identique.

Bien que cet ouvrage traite plus des meules artificielles, on trouve une colonne de texte sur les meules naturelles.

Dictionnaire de Justin Storck

L'entrée meule du dictionnaire de Justin Storck évoque les meules en grès et en émeri.

Un petit article sur le grès également.

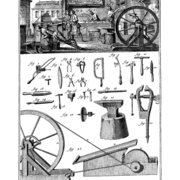

Encyclopédie Diderot et d'Alembert

Grès

GRAIS, ou GRÈS, (Hist. nat. Minéralogie.)

Meule

MEULE, (Art. méchaniq. & Gramm.)

On y retrouve la méthode d'extraction illustrée par la vidéo du premier article.

Description de l'emploi de coins en bois blanc, arrosés d'eau pour les faire gonfler et ainsi détacher la meule dans la carrière après avoir taillé le tour sur place.

Les meules à aiguiser des Taillandiers & des Fourbisseurs sont les plus grandes qui s’emploient : plus un instrument à émoudre est large & doit être plat, plus la meule doit être grande ; car plus elle est grande, plus le petit arc de sa circonférence sur lequel l’instrument est appliqué tandis qu’on l’aiguise, approche de la ligne droite.

Il y a des meules à aiguiser de toutes grandeurs : elles sont de grès ni trop tendre ni trop dure ; trop tendre, il prendroit trop facilement l’eau dans laquelle la meule trempe en tournant : la meule s’imbiberoit jusqu’à l’arbre sur lequel elle est montée, & la force centrifuge suffiroit pour la séparer en deux, accident où la perte de la meule est le moins à craindre : l’ouvrier peut en être tué. Si elle ne se fend pas, elle s’use fort vîte. Trop dure, & par conséquent d’un grain trop petit & trop serré, elle ne prend pas sur le corps dur & ne l’use point.

Il est important que la meule sur laquelle on émout trempe dans l’eau par sa partie inférieure : sans cela le frottement de la piece sur elle échaufferoit la piece au point qu’elle bleuiroit & seroit détrempée.

Je m'égare...

Article Menuiserie et planches associées.

Ce pas à pas présente un projet en cours de réalisation.

Discussions

Que de souvenirs de mon apprentissage !! La meule a eau y a pas mieux traditionnellement !

Seulement avec les aciers modernes au chrome, je trouve que ça peine un peu. En tout cas, j'ai fait le constat sur un ciseau Goldenberg récent et un fer Darex... Peut-être que mon grès n'est pas terrible...

Grès à ciment calcaire ou siliceux ? si calcaire, moins costaud, plus friable.

Ybos je ne sais pas. Tu peux voir des vues en détail dans ma création associée. Je veux bien des infos si tu en as !

Après le ciment n'est que le liant. Je n'ai pas l'impression qu'elle soit "trop" friable ni "trop peu" d'ailleurs.

salut dans la video sur l'extraction des meules, je pencherait plutot pour des meules destinées a des moulins