Ouvrage

Contenu

Résumé

When it comes to exploring the shadowy history of how 17th-century furniture was built, few people have been as dogged and persistent as Jennie Alexander and Peter Follansbee.

For more than two decades, this unlikely pair – an attorney in Baltimore and a joiner at Plimoth Plantation in Massachusetts – have pieced together how this early furniture was constructed using a handful of written sources, the tool marks on surviving examples and endless experimentation in their workshops.

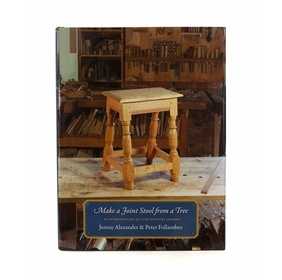

The result of their labor is “Make a Joint Stool from a Tree: An Introduction to 17th-century Joinery.” This book starts in the woodlot, wedging open a piece of green oak, and it ends in the shop with mixing your own paint using pigment and linseed oil. It’s an almost-breathtaking journey because it covers aspects of the craft that most modern woodworkers would never consider. And yet Alexander and Follansbee cover every detail of construction with such clarity that even beginning woodworkers will have the confidence to build a joint stool, an iconic piece of furniture from the 17th century.

Joint stools are a fascinating piece of British and early American furniture. Made from riven – not sawn – oak, their legs are typically turned and angled. The aprons and stretchers are joined to the legs using drawbored mortise-and-tenon joints, no glue. And the seat is pegged to the frame below. Because of these characteristics, the stools are an excellent introduction to the following skills.

• Selecting the right tools: Many of the tools of the 17th century are similar to modern hand tools – you just need fewer of them. “Make a Joint Stool from a Tree” introduces you to the very basic kit you need to begin.

• Processing green oak: Split an oak using simple tools, rive the bolts into usable stock and dry it to a workable moisture content.

• Joinery and mouldings: Learn to cut mortises and tenons by hand, including the tricks to ensure a tight fit at the shoulder of the joint. Make mouldings using shop-made scratch stocks – no moulding planes required.

• Turning: Though some joint stools were decorated with simple chamfers and chisel-cut details, many were turned. Learn the handful of tools and moves you need to turn period-appropriate details.

• Drawboring: Joint stools are surprisingly durable articles of furniture. Why? The drawbored mortise-and-tenon joint. This mechanical joint is rarely used in contemporary furniture. Alexander and Follansbee lift the veil on this technique and demonstrate the steps to ensure your joint stool will last 400 years or so.

• Finishing: Many joint stools were finished originally with paint. You can make your own using pigments and linseed oil. The right finish adds a translucent glow that no gallon of latex can ever provide.

“Make a Joint Stool from a Tree” is also the long-awaited follow-up to Alexander’s 1978 book “Make a Chair from a Tree,” which has been out of print for many years. “Make a Chair from a Tree” inspired generations of woodworkers to pick up hand tools and the skills required to use them. That book was one of the essential sparks that ignited the resurgence of handwork we are experiencing today.

This new book – "Make a Joint Stool from a Tree” – is sure to inspire many more and give woodworkers a fuller understanding of how furniture can and should be made with hand tools.

Like all Lost Art Press books, “Make a Joint Stool from a Tree” is printed in the United States on acid-free paper with a sewn binding. This 128-page book is in full color, with more than 200 photos and a dozen illustrations. “Make a Joint Stool from a Tree” is in an oversized 9” x 12” format, covered in dark blue cloth and has a full-color dust jacket.

For more than two decades, this unlikely pair – an attorney in Baltimore and a joiner at Plimoth Plantation in Massachusetts – have pieced together how this early furniture was constructed using a handful of written sources, the tool marks on surviving examples and endless experimentation in their workshops.

The result of their labor is “Make a Joint Stool from a Tree: An Introduction to 17th-century Joinery.” This book starts in the woodlot, wedging open a piece of green oak, and it ends in the shop with mixing your own paint using pigment and linseed oil. It’s an almost-breathtaking journey because it covers aspects of the craft that most modern woodworkers would never consider. And yet Alexander and Follansbee cover every detail of construction with such clarity that even beginning woodworkers will have the confidence to build a joint stool, an iconic piece of furniture from the 17th century.

Joint stools are a fascinating piece of British and early American furniture. Made from riven – not sawn – oak, their legs are typically turned and angled. The aprons and stretchers are joined to the legs using drawbored mortise-and-tenon joints, no glue. And the seat is pegged to the frame below. Because of these characteristics, the stools are an excellent introduction to the following skills.

• Selecting the right tools: Many of the tools of the 17th century are similar to modern hand tools – you just need fewer of them. “Make a Joint Stool from a Tree” introduces you to the very basic kit you need to begin.

• Processing green oak: Split an oak using simple tools, rive the bolts into usable stock and dry it to a workable moisture content.

• Joinery and mouldings: Learn to cut mortises and tenons by hand, including the tricks to ensure a tight fit at the shoulder of the joint. Make mouldings using shop-made scratch stocks – no moulding planes required.

• Turning: Though some joint stools were decorated with simple chamfers and chisel-cut details, many were turned. Learn the handful of tools and moves you need to turn period-appropriate details.

• Drawboring: Joint stools are surprisingly durable articles of furniture. Why? The drawbored mortise-and-tenon joint. This mechanical joint is rarely used in contemporary furniture. Alexander and Follansbee lift the veil on this technique and demonstrate the steps to ensure your joint stool will last 400 years or so.

• Finishing: Many joint stools were finished originally with paint. You can make your own using pigments and linseed oil. The right finish adds a translucent glow that no gallon of latex can ever provide.

“Make a Joint Stool from a Tree” is also the long-awaited follow-up to Alexander’s 1978 book “Make a Chair from a Tree,” which has been out of print for many years. “Make a Chair from a Tree” inspired generations of woodworkers to pick up hand tools and the skills required to use them. That book was one of the essential sparks that ignited the resurgence of handwork we are experiencing today.

This new book – "Make a Joint Stool from a Tree” – is sure to inspire many more and give woodworkers a fuller understanding of how furniture can and should be made with hand tools.

Like all Lost Art Press books, “Make a Joint Stool from a Tree” is printed in the United States on acid-free paper with a sewn binding. This 128-page book is in full color, with more than 200 photos and a dozen illustrations. “Make a Joint Stool from a Tree” is in an oversized 9” x 12” format, covered in dark blue cloth and has a full-color dust jacket.

Détails

Cette fiche est complétée et contrôlée collaborativement par la communauté. Si vous détectez des erreurs ou des manques, apportez vos propositions !

Critiques

Ce livre ne possède pour l'instant aucune critique de lecteur.

Soyez le premier à ajouter la votre !

Soyez le premier à ajouter la votre !

Connectez-vous pour ajouter votre critique.

Vous n'êtes pas autorisé à indiquer votre accord ou désaccord vos propres contributions.

L'adresse e-mail associée à votre compte doit être confirmée avant de pouvoir indiquer votre accord ou désaccord.

Chargement...

Chargement...

Publications associées

0

collection

Discussions